In a 2021 issue of the historical journal Quaderni di Storia (no. 93), Luciano Canfora’s editorial included a short essay by the German ancient historian, Stefan Rebenich. Rebenich’s essay was itself written in response to recent statements of anti-racism made by classicists in the USA, in the wake of the horrific murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Rebenich also fixes in his sights a paper delivered by the Princeton classicist Dan-el Padilla Peralta at a panel on “The Future of Classics” at the US-based Society for Classical Studies (SCS) Annual Meeting at San Diego, California in January 2019.

Rebenich does not deny the need for classical scholarship to confront the complicities of classical studies in projects of social exclusion and racial discrimination. What Rebenich objects to is the “reductionist conception” of western civilisation and what he describes as “the fight against the predominance of the white man”, evidenced by Padilla Peralta’s paper. Rebenich homes in on a particular element of Padilla Peralta’s argument, namely that white men take a back seat to people of colour, specifically women and gender-nonconforming scholars of colour, when it comes to publications. Rebenich attacks this apparent refusal of the principle of double-blind peer-review, the process by which the identities of both author of an article and its reviewers are mutually anonymised. Yet what Padilla Peralta refers to is the editorial process, stages of review which are not anonymised, and backs up his arguments with statistics on a gross imbalance in racial backgrounds of published authors of three key US Classics journals. Rebenich characterises Padilla Peralta’s argument as “reverse racism” with totalitarian tendencies. He closes by mentioning an open letter signed by 200 students of the Oxford University Classics faculty, demanding compulsory racial bias training for staff (an unremarkable demand) and what Rebenich describes as “a preferential path to be offered to ‘people of colour’ to obtain a place [of study]”. “Of course, this is the thought of a white man”, Rebenich writes, “but it is not, for this reason, false”.

Canfora’s presentation of Rebenich’s article skilfully elides the context from which Padilla Peralta’s intervention emerges, as well as the evidence which leads the Princeton scholar towards his conclusions. Thankfully, Padilla Peralta’s paper, delivered to the SCS 2019 annual meeting, is also reprinted in this same issue of Quaderni di Storia. In order to contextualise this annual meeting for non-classicists, I should note that this annual event is one of the largest and most high-profile conferences for the disciplines of Classics and Classical Archaeology globally, and this particular meeting saw BIPOC participants racially profiled and subjected to insulting identity checks, an event acknowledged in Padilla Peralta’s paper. In the paper, Padilla Peralta goes through data assembled on the racial backgrounds of published Classics scholars, closing with the admittedly provocative suggestions, attacked by Rebenich. A more careful reading of Padilla Peralta’s conclusion, however, amounts to a compelling demand: that “holders of privilege will need to surrender that privilege”. It is the problem of academia, existing as a zero-sum “economy of academic prestige defined and governed by scarcity” based on publication, which excludes non-white scholars, that Rebenich ignores.

Canfora’s editorial and introduction to Rebenich’s essay, then, engages with these two contexts: the statements of classicists in support of Movements for Black Lives; and Padilla Peralta’s paper at SCS 2019. Canfora opens his introduction to Rebenich’s essay by noting the dominance of the USA in conversations about racism and Classics, suggesting that the USA stands out as country where not only does racism have deep roots, but where it is openly promoted in political rhetoric. In order to suggest that a myopic focus on the US gives a warped view of the discipline, Canfora points to examples of what he sees as Classics’ tendency towards “auto-decolonisation”. Among these moments, Canfora cites the “Quarrel of Ancients and Moderns”, a long debate in early modernity, mostly in France, on whether looking to the ancient Greeks and Romans held the key to what is best for society or whether a decisive rupture from the cult of antiquity promised a brighter future. Following the triumph of Enlightenment rationalism, another moment cited as “auto-decolonisation”, came the Romantic reaction, its melancholic poetics inspired by the ruins of classical antiquity. Fast-forwarding to Quaderni di Storia’s own contribution to this auto-decolonising tendency, Canfora highlights work published in this same journal examining Fascist and National Socialist uses of classical antiquity. Canfora himself has been a prolific voice in this area of scholarship, the author of the 1980 monograph Ideologie del classicismo, one of the most important studies of Fascism’s use of the ancient world.

Yet what remains striking in Canfora’s suggestion of Classics’ “auto-decolonisation” is the absence of an acknowledgement of Classics’ much better evidenced complicity in processes of colonisation. Indeed, for a discussion of purported “auto-decolonisation” of Classics, the lack of any mention of colonialism, colonisation, or imperialism invites examination. Canfora, as author of numerous works on the interaction between Italian Fascism and Roman antiquity, is an expert on the amenability of the discipline to oppressive ideologies, and so his silence on the matter of Classics and colonialism must be a conscious one. Moreover, given that this is an introduction to what amounts to a refutation of Padilla Peralta’s paper on Classics and racism, the absence of reference to Classics’ role in upholding racist structures outside of the US suggests that this is a problem that does not exist in Europe, or indeed, Italy. This silence is particularly striking for an Italian historical journal. It remains to be seen, therefore, in Canfora’s introduction to Rebenich’s essay, what the relationship between Classics, racism, and colonialism is in Italy.

Classics and ancient history had an important place in the self-representation of the Italian nation during and after its unification in the second half of the nineteenth century. As scholars such as Antonino De Francesco, Andrea Avalli, and Henrik Mouritsen show, it was not just Roman history that held appeal for nationalist, and then Fascist, discourses on Italian ancient history, but Etruscan too. However, Roman antiquity did hold a powerful grip on the Italian national imaginary in the decades following Italian unification, and through into the Fascist era. This extended to the formulation of colonial and racist ideologies. Since it is often easy for classicists, ancient historians, and classical archaeologists to shrug off non-specialist, political uses of classical antiquity as historically illiterate, inaccurate, and generally ignorant, I will focus on a few key examples of when the academic disciplines of Classics, Ancient History, and Classical Archaeology were brought into the service of Italian colonialism and racist ideologies.

Appeals to ancient Roman history became increasingly pronounced when the young Italian nation launched into a colonial enterprise in East Africa in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. For example, in 1883, the renowned archaeologist, Rodolfo Lanciani, unearthed an obelisk dating from the reign of Rameses II during excavations at the former site of the Isaeum, a religious sanctuary devoted to the Egyptian goddess Isis, in Rome. This obelisk had been brought to Rome by the emperor Domitian. Soon after the defeat at Dogali, inflicted on Italian colonial troops in Ethiopia in 1887, it was decided that this obelisk should be erected as a monument in commemoration of this military disaster. Thus, it was that this monolith, brought into Rome as imperial plunder by the empire of the Caesars, had now been repurposed as a monument to modern Italian imperial ambitions. With the names of the five-hundred Italian soldiers who had been killed at Dogali inscribed on the faces of this monolith, this Egyptian obelisk, brought into Italy by ancient Roman imperialism, was the only one to be set up in Rome as the capital of the new nation-state. The story of this obelisk, which can be seen near Roma Termini today, is deeply implicated in the history of early Italian colonialism in Africa.

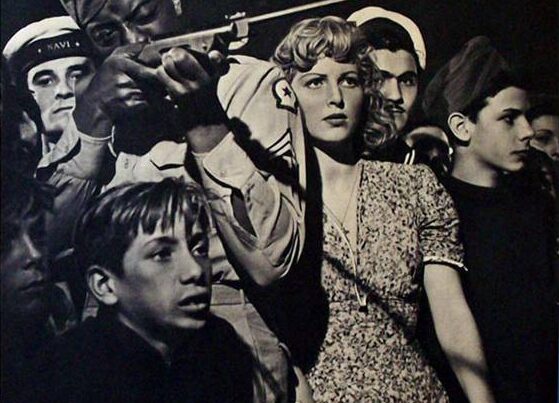

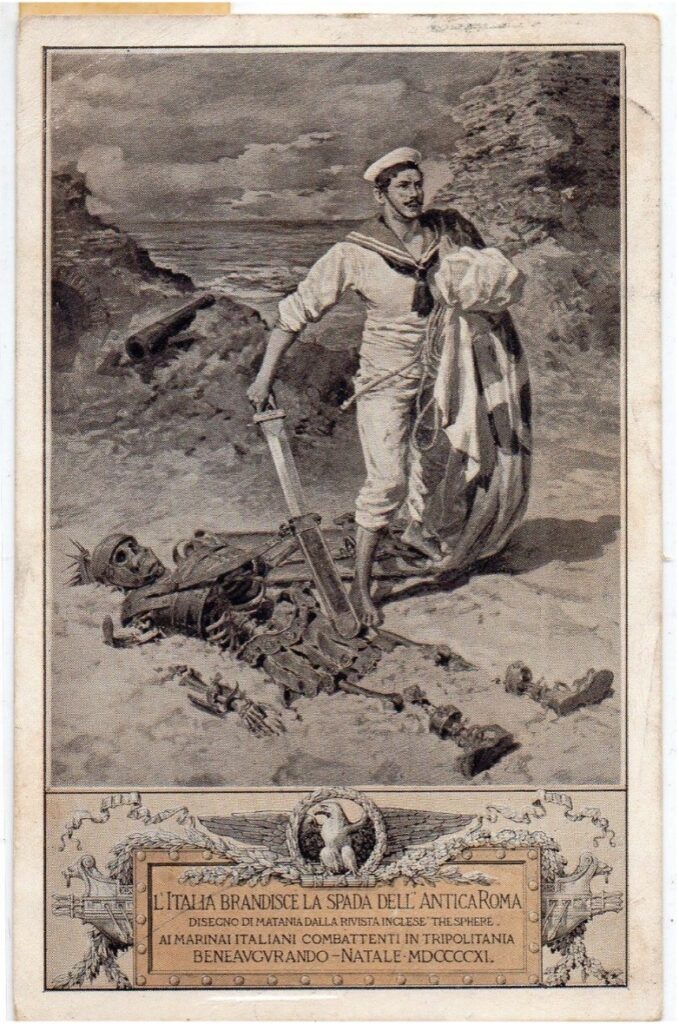

It was with Italy’s later invasion of the Libyan provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, in 1911-1912, that we see the academic disciplines of Classics, Ancient History, and Archaeology start to more explicitly be brought into the service of colonialism. This phenomenon was especially pronounced due to the fact that Libya had been a province of the Roman empire, and that the North African region contained some of the best preserved Roman archaeological sites.[1] The notion of North African populations being inadequate custodians of the region’s classical heritage, and the natural right of the Italian “race” (stirpe) to North Africa became a common trope in Italian imperial propaganda of this time. The period of Italy’s invasion of Libya also saw celebrations of Roman imperialism circulating more widely in academic and popular contexts. For example, in 1911, to coincide with celebrations of the fiftieth anniversary of Italian unification, an exhibition was staged at Rome’s Baths of Diocletian, on imperial Rome’s provinces, including Libya and North Africa, curated by Lanciani. In addition, references to Roman antiquity in Libya were made frequently in Italian visual culture of the period, including paintings, such as “Italy draws the sword of ancient Rome” by Eduardo Matania (fig. 1), medallions, and films, such as the classic of Italian silent cinema Cabiria (dir. Giovanni Pastrone, 1914).

It would be later, under Fascism, that the links between Classics and Ancient History, racism, and colonialism would become most pronounced. However, it is important to stress that, far from Fascism’s uses of antiquity being an anomaly or innovation, Mussolini’s movement built on liberal colonial discourses. While Canfora’s citation of articles on Fascist classicisms, published in Quaderni di storia, as evidence of the discipline’s “auto-decolonisation”, implies that Fascism’s use of antiquity contributed to the “colonisation” of the discipline, it would be wrong to suggest that the ideology’s influence on the study of the ancient Mediterranean has been totally expunged.

I will begin with the most well-known examples of Fascism’s use of Italy’s Roman past: the so-called “Roman salute”, the straight-armed, palm-down gesture used by the far-right to this day; the fasces, the symbol of ancient Roman lictors; the spectacularism and ceremonial of Mussolini’s movement. These elements of Fascism’s appropriation of Roman antiquity are familiar enough and easy to dismiss as purely symbolic or erroneous. However, the complicities and compromises of the academic study of classical antiquity and Fascism are less easy to dismiss.

The Istituto di Studi Romani (I.S.R.) was an institution founded under Carlo Galassi Paluzzi, a close friend of Fascist cultural minister Giuseppe Bottai, in 1925, from the journal Roma: rivista di studi e di vita romana, established two years earlier. The institution’s mission was the development and diffusion of the study and knowledge of Rome, emphasising the interconnectedness of the three Romes: ancient, Christian, and Fascist, a mission closely aligned with the interests of the Fascist regime. Galassi Paluzzi saw the institution as “an army on the march”, obeying the king and il Duce in service of the goal of the “victorious rebirth of the idea of Rome”. The published activities of the Istituto show an increasing preoccupation with the promotion of Italian colonialism in Africa from its institution in 1925, reaching a peak in the years between 1935 and 1938, the years of and closely following the invasion of Ethiopia (1935-1936). Indeed, a 1936 article in Roma extolled the ideological support given to imperialism in Africa through study of Roman antiquity on the continent.

The I.S.R., now the Istituto Nazionale di Studi Romani, continues to be an important research body in the study of the ancient and medieval city of Rome. Its website makes only one oblique reference to the ideological foundations of the institute to state that “in August 1944, after the liberation of the city [Rome], [Galassi Paluzzi] was replaced as the president of the Istituto di Studi Romani by a commissioner, because of his compromise with the Fascist regime”.[2] The foundations of the I.S.R have been studied by scholars such as Mariella Cagnetta and Luciano Canfora, and have continued to be explored in depth by researchers including Jan Nelis, Han Lamers and Bettina Reitz-Joosse, showing the deep and complex links between Fascism’s ideological emphasis on ancient Roman history and research on Roman antiquity from that period. This is not, of course, to say that research under the auspices of the I.S.R. is all tainted by Fascism. Indeed, scholars such as Arnaldo Momigliano, who later fled Fascist Italy, were involved with the I.S.R. However, the Institute’s indebtedness to Fascism’s interest in ancient Roman history must be acknowledged.

There were, however, prominent scholars of classical antiquity who did take an active role in promoting the colonial agenda of Fascism. Nicola Festa, Professor of Greek at the University of Rome, La Sapienza, was one such figure. Besides his important academic work, Festa is also well-known for translating a number of Mussolini’s speeches, concerning the invasion of Ethiopia, into Latin. Recently, scholars including Han Lamers, Bettina Reitz-Joosse, and Antonino Nastasi have shown how Latin was mobilised as an ideological tool by Italian Fascism.[3] It was seen by the regime as the language of “past-anchored renewal”, suitable for monumentalising the present for the future, since the Romans, according to Vicenzo Ussani, Latin philologist at Sapienza, had “looked to the future while looking to the past”. Aurelio Giuseppe Amatucci, another Latinist and author of the Codex Fori Mussolini, a Latin text written in 1932 and narrating Fascism’s first ten years in power,[4] had theorised that only Latin could express Fascism’s idea of the future, and come to function as a common language for Italy and her empire. The speeches of Mussolini which Festa translated had been delivered to crowds gathered at Piazza Venezia between 1935 and 1936, and culminated in the proclamation of the foundation of a new Fascist Roman empire. Years in Italy began to be measured ab imperio condito (from the foundation of empire), in addition to years being counted from the Fascist revolution and with anno domini.

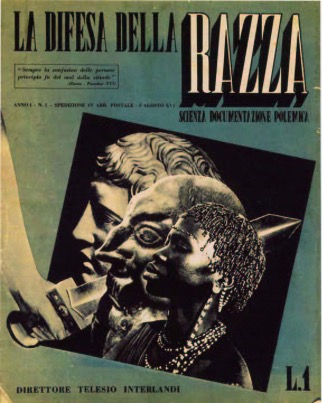

In the latter years of the 1930s and the run-up to the Second World War, Italian Fascism became increasingly explicitly racist and antisemitic. The journal La Difesa della Razza (The Defence of the Race), founded in 1938, bears testament to the uses of classical antiquity in promoting Fascism’s racist policies (fig. 2). Numerous articles posed Fascist racism as a revival of ancient Roman theories of race. Roberto Bartolozzi, who translated Thomas More’s Utopia from Latin into Italian and also wrote a highly ideological book on Roma e Augusto (Rome and Augustus, 1938), wrote a series of racist and antisemitic articles in La Difesa della Razza on Roman antiquity. Examples include articles arguing for “the racism of Caesar”, who emphasised the connection between the Italian stirpe and the Italian land and another on Cato the Elder who advised his compatriots, according to Bartolozzi as follows:

Romans, conserve intact your birth, pure your language, whole your ancient customs. Don’t leave yourself open to be contaminated by barbarians, nor your civilisation to be ceded to them.[5]

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the conflict was at times framed with reference to Roman antiquity, including in the academic realm. The prominent classicist Ettore Pais had characterised the British Empire as the new Carthage, the nemesis of mid-Republican Rome, as early as 1938, and such rhetoric grew in prominence once war between Britain and Italy was declared in 1940. For example, a pamphlet published by the I.S.R. in 1940, entitled I moderni carthagi argues that both Britain and Carthage were driven by mercantile individualism, over which the new Rome of Fascist Italy is destined to triumph. Elsewhere, in publications such as La Difesa della Razza, the purported Semitic links between Carthage and modern Jewish communities in Europe were turned into rhetorical tools for Fascist antisemitism.

After the fall of Fascism, it became easy to associate Italian colonialism and official racism with the defeated ideology, meaning that discussions of Italy’s colonial history became largely suppressed. After all, Mussolini had been deposed and Italy liberated. Such reluctances to see the continuities between pre-Fascist, Fascist, and post-Fascist ideologies of classicism have contributed to the denial of the continuing links between classical antiquity, racism, and colonialism in Italy today. Not only do many of Fascism’s classicising monuments, often inscribed with Latin, remain standing, but the contemporary far-right in Italy frequently frame their racism and neo-Fascism with reference to Roman antiquity. For example, the neo-Fascist movement Casa Pound’s emblem is a tortoise, referencing the testudo formation of the Roman army. The very real consequences of ongoing uses of Classics in promoting racist ideologies, not only in Italy, means that classicists do not have the luxury of relying on what Canfora sees as the discipline’s “auto-decolonisation”, but should proactively and energetically confront the history of the discipline’s active support of racism and colonialism. Of course, this is an uncomfortable process which demands that difficult questions be asked about the responsibilities of classicists today. It is little wonder, therefore, that Padilla Peralta’s intervention has provoked such defensiveness as seen in Rebinich’s essay and Canfora’s editorial.

[1] See Massimiliano Munzi, L’Epica del Ritorno: Archeologia e politica nella Tripolitania Italiana (Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2001), or for an English language summary, Massimiliano Munzi “Italian Archaeology in Libya: From Colonial Romanità to Decolonisation of the Past”, in Archaeology under Dictatorship, ed. Michael Galaty and Charles Watkinson (New York: Springer, 2004), 73-107.

[2] http://www.studiromani.it/il-fondatore.html [accessed 2nd July 2021].

[3] See Lamers new research project, New Signs of Antiquity (https://www.hf.uio.no/ifikk/english/research/projects/new-signs-of-antiquity-the-uses-of-latin-in-the-pu/index.html)

[4] See Han Lamers and Bettina Reitz-Joosse, The Codex Fori Mussolini: A Latin Text of Italian Fascism (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)

[5] Roberto Bartolozzi, “Razzismo di Catone Maggiore,” La Difesa della Razza 2, no. 2 (1938), 20-21.