During the Anglo-American occupation of Italy (1943-1954), the participation of African American troops in the theatre of operations provided the occasion for unprecedented encounters with local civilians. The issue of how that was judged by the Italian public and popular opinion is still being debated. It was recently argued that the dual legacy of colonial/Fascist racism on the one hand, and the anti-Italian sentiment in urban African American communities nourished by the Fascist war on Ethiopia on the other hand, did not prevent black liberators and Italian people from having positive, ‘unofficial’ interactions based on familiarization, mutual fascination and even empathy[1]. Furthermore, a sense of shared experience between black Americans and the poor, ‘good Italians’ recovering from the WWII catastrophe was revived by left-wing, anti-Fascist intellectuals such as Giorgio Caproni, who promoted a powerful though victimisation rhetoric speaking of “offended people drawn towards other offended people”[2].

The analysis of the relationships between African American GIs (a label referring to US soldiers) and Italian illegal prostitutes adds actually a further, important piece to this complex picture, and offers a thought-provoking perspective on the ways anti-black racism still shaped the Italian mainstream national culture in the post-Fascist transition. At the turn of the military occupation, a particular type of sex work spread. This was represented by the so-called ‘segnorine’, a neologism that emblematically gained currency to ‘otherize’ Italian women working outside the system of state controlled sex work (providing for brothels or the status of librettate) and specifically selling sex to American soldiers. The dangerous liaisons between the segnorine and the African Americans soon became a widespread, negative trope in the Italian press, novels and neorealist films, to the point that their media hype fuelled popular reactions of hostility and even mob violence.

These clandestine prostitutes were generally blamed for compromising the integrity of Italian pride, male honor and bloodline, while refusing to comply with bourgeois gender roles and regulationist standards. Livorno with its neighbouring area represents the most interesting case for highlighting the intersection between race and gender in post-war reconstruction of national identity. The pine forest of Tombolo situated between Pisa and Livorno emerged as a gigantic army remittance for the 10th Port, based in Livorno from September 1, 1944, to December 31, 1947. In fall 1944, Tombolo also became a rendezvous land for the 92nd Infantry Division (the ‘Buffalo’, i.e. the only segregated African American division fighting in Europe and employed in the assault on the Gothic Line). This area, which was made famous and popularized by a number of neorealist films, was scattered with supply depots. There, troop camps coexisted with irregular elements and deserters, black market and smuggling. For this reason, it turned into a quintessential site of feminine degeneration and deviance, as it was presented as an equivocal place of forbidden racial interactions between the victors and the occupied, the black Americans and the white Italians.

Tombolo can be interpreted as a “contact zone”, where “peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations, usually involving conditions of coercion, radical inequality, and intractable conflict”[3]. Imagined as a “paradiso nero” (black paradise), and consequently as a hell of perdition for Italian women, the pine forest was a common theme in several films, novels and journalistic reports. Between 1946 and 1954, more than one hundred articles about the segnorine were published in the pages of the most important Italian newspaper, the conservative Corriere della Sera, focusing above all on Livorno and Tombolo. But also l’Unità, that is the organ of the Italian Communist Party, paid great attention to this topic, blaming these women for their relaxed morality, corrupted by the fascination for the US model of capitalistic consumerism. Local newspapers of different political orientation were involved in xenophobic reports denouncing prostitutes and describing them as aliens and foreigners to the city, to be sent back to their own homes.

The narratives about the segnorine combined two forms of racism: the one against southern migrant women and the one against African American soldiers. Southern identity was sometimes interpreted as a sufficient reason to suspect that a woman was a prostitute. Information about the southern background of the segnorine was also given by the local National Liberation Committee (CLN), which asked for the expulsion from Livorno of the so-called “undesirable guests”, criminals of any sort and those coming from the Meridione in order to prostitute themselves[4]. In the part of Italy where the ‘Northern wind’ blew, the anti-southern prejudice developed again, on a municipal scale, by consolidating the classic ethnocentric stereotypes about Campania, Calabria, Basilicata, Sicily and Sardinia. These regions were considered the bearers of a backward civilization, a lazy culture, a primitive lifestyle and an atavistic delinquency. The upsurge in crime was therefore explained by projecting onto the South the moral decay and social unrest of the post-war reconstruction. In an interweaving of local identity and national identity, a sub-race of ‘bad Italians’ was sacrificed to save the good name of the emerging democracy made by ‘good Italians’.

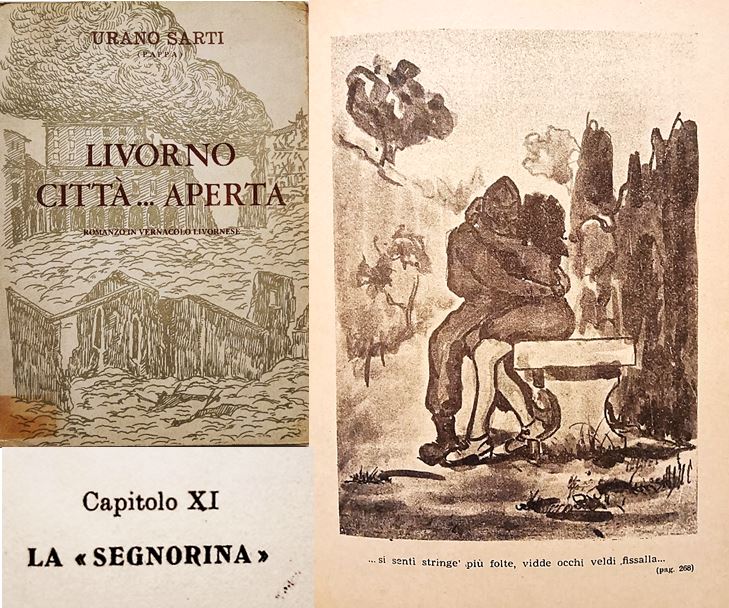

Both right-wing and leftist Italian newspapers were also full of references to the race of prostitutes’ customers. However, African Americans were generally described in a different way than African inhabitants of colonies or colonial troops. The latter, also because of the rapes committed by French-Moroccan troops in the area of Cassino and on Elba Island, were typically represented as brutal savages. The characterization of African Americans in the discourse on the segnorine was less negative instead. They were generally described as good, childish simpletons, led by instinct and irrationality, often drunk and always eager for white women. Nevertheless, a unifying trait was the haunting fear of miscegenation. Few examples are sufficient to clarify the narratives spread by the press. On September 14, 1946, the front page of l’Unità hosted an article titled Ohè, Joe! Qui si è più liberi che in America! [Hey, Joe! Here we are freer than in America!]. The article was a harsh denunciation of the price to pay by Italians for the Allied occupation, and described the “Negro soldiers” as “preys to an ancestral inferiority complex”. The journalist polemically denounced Jim Crow discrimination in the United States targeting white Americans compared to Italian greater tolerance, but ended up expressing some racist clichés – as paternalistic as dehumanizing – that depicted blacks as immature children, or similar to funny chimpanzees on a carousel. Everybody knew – the article said – that the “negroes” were basically “good, that they like to hang out with white people, that you have to make them drink, but not too much otherwise they become crazy and are dangerous” [5]. Such a description did not differ so much from the classic theme of the innate mental inferiority of the ‘Negro’ claimed a few years before by Fascist racist literature, even if this time the focus was not on the biological inferiority of African-descended people. Nevertheless, the portrayal of the black character incorporated a well-established anthropological tradition, looking at the ‘Negro’ as cheerful, childlike, backward, ultimately alien to civilization. The continuity between post-Fascist cultures and colonial racism was evident.

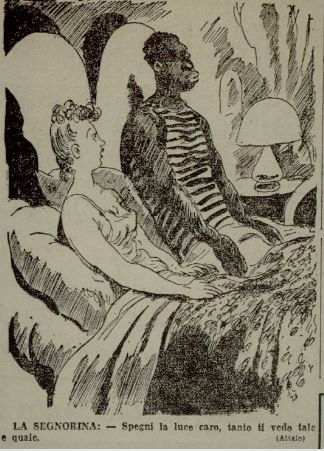

Moreover, the anti-segnorine rhetoric and the related anti-black sentiment were largely popularized across political lines. The dissemination of racist-sexist, derogatory stereotypes was not only distinctive of the conservative, ‘moderate’ and ‘anti-anti-Fascist’ intelligentsias, not to mention the those nostalgic of the Fascist regime. It was also undertaken by the left-oriented press, as the satirical weekly Il Pettirosso published in Rome, as a subsidiary of the mouthpiece of the Italian Socialist Party Avanti!, shows. ‘Humorous’ cartoons and stories making fun of the segnorine and African Americans regularly appeared in the magazine between 1945 and 1947. The mocking image of a black GI forced to wear shoes making him uncomfortable because of his savagery, while impoverished Italian civilians wore sandals or were barefoot[6], was really emblematic of the point of view of the magazine.

In Socialist and Communist sources, the ridicule of black servicemen and segnorine joined the anti-American and anti-consumeristic way of life, often prevailing over denigration founded on outspoken contempt or demonization. While the language of national-patriotism was not lacking at all, that discourse combined with the idea that the women selling sex to the Americans were “the expression of a moral fatigue, a longing for a more prosperous life”[7]. The fact remains the Left anti-American mood resulted in anti-black racist trivializations which were reported by the African American press and even by the US military newspaper Stars and Stripes. The war correspondent of the Baltimore Afro-American – a black officer belonging to US infantry troops in Italy – denounced the “offensive cartoon” entitled “Shoes” as an insult to “every coloured soldier and every coloured American”. Stars and Stripes stated that the “coloured American is not a stranger to shoes”, nor to the “ideas of democracy”, and that a Socialist newspaper was supposed to fight “against, and not for” Hitler’s Nazi racism[8].

Coming to a conclusion, the icon of the segnorina perfectly emphasizes the post-war contradictions mixing democratic egalitarianism, discriminatory clichés, patriotic anti-Fascism, anti-southern bias and anti-Americanism. The interplay between gender, race and crime, so well described by the relationships between black GIs and Italian prostitutes, also seems to be a perfect key to show how the marginalization of some particular groups of people – a degenerate humanity, animated by bad women coming from Southern Italy and their African American lovers – was pivotal for rebuilding the respectability of Italian democracy, reaffirming the honour of the nation, and whitewashing national identity by leaving behind the moral faults of Fascism, the ruins of war, and the shadow of defeat which was epitomised by the peculiar image of the ‘Allied invader’, even more obnoxious when intersectionally associated with the inferiorizing stigma of blackness and southerness.

[1] C. O’Connell, “A Roman Holiday? African Americans and Italians in the Second World War”, History: The Journal of Historical Association, no. 373 (2021): 775-803.

[2] C.L. Leavitt IV, “Impegno nero: Italian Intellectuals and the African-American Struggle”, California Italian Studies, no. 2, 2013, https://doi.org/10.5070/C342013561.

[3] C.L. Leavitt IV, “The Forbidden City: Tombolo between American Occupation and Italian Imagination”, in G. Bonsaver, A. Carlucci and M. Reza (eds.), Italy and the USA: Cultural Change Through Language and Narrative (Cambridge: Legenda, 2019), 148.

[4] “Dopo la sparatoria di Via Pellegrini – Vivace campagna contro l’immigrazione di ospiti indesiderabili”, Il Tirreno, July 25, 1945.

[5] “Quanto ci costa l’occupazione alleata. I negri sulla giostra. ‘Ohè, Joe! Qui si è più liberi che in America!’”, l’Unità, August 14, 1946.

[6] Il Pettirosso, February 4-10, 1945.

[7] Franco Ferrarotti, quoted in C. Fantozzi, “L’onore violato: stupri, prostituzione e occupazione alleata (Livorno 1944-47)”, Passato e Presente, no. 99 (2016): 102.

[8] M. Johnson, “GI’s Await Army’s Action on Italian Paper’s Insult”, Baltimore Afro-American, February 10, 1945.

This article received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 84336.