Since the late 1970s, Italian classicists like Mariella Cagnetta, Luciano Canfora and Andrea Giardina have been studying the Fascist myth of ancient Rome. Moreover, in recent years, historians of Fascism like Roger Griffin, Emilio Gentile, Aristotle Kallis, Paola Salvatori and Joshua Arthurs have reflected on the Italian relationship with its classical past by studying the history of archaeology, contemporary art and architecture as sources to understand Fascist ideology. Since the myth of ancient Rome has been widely interpreted by classicists and historians, through my PhD research (2016-2020) I tried to extend this approach to an analysis of the political uses of the Etruscan identity under Fascism. As an ancient people who were enemies of ancient Rome and historically associated with a regional identity, the Etruscan case can enlighten the ambiguous, socially constructed features of Italian nationalism and racism.

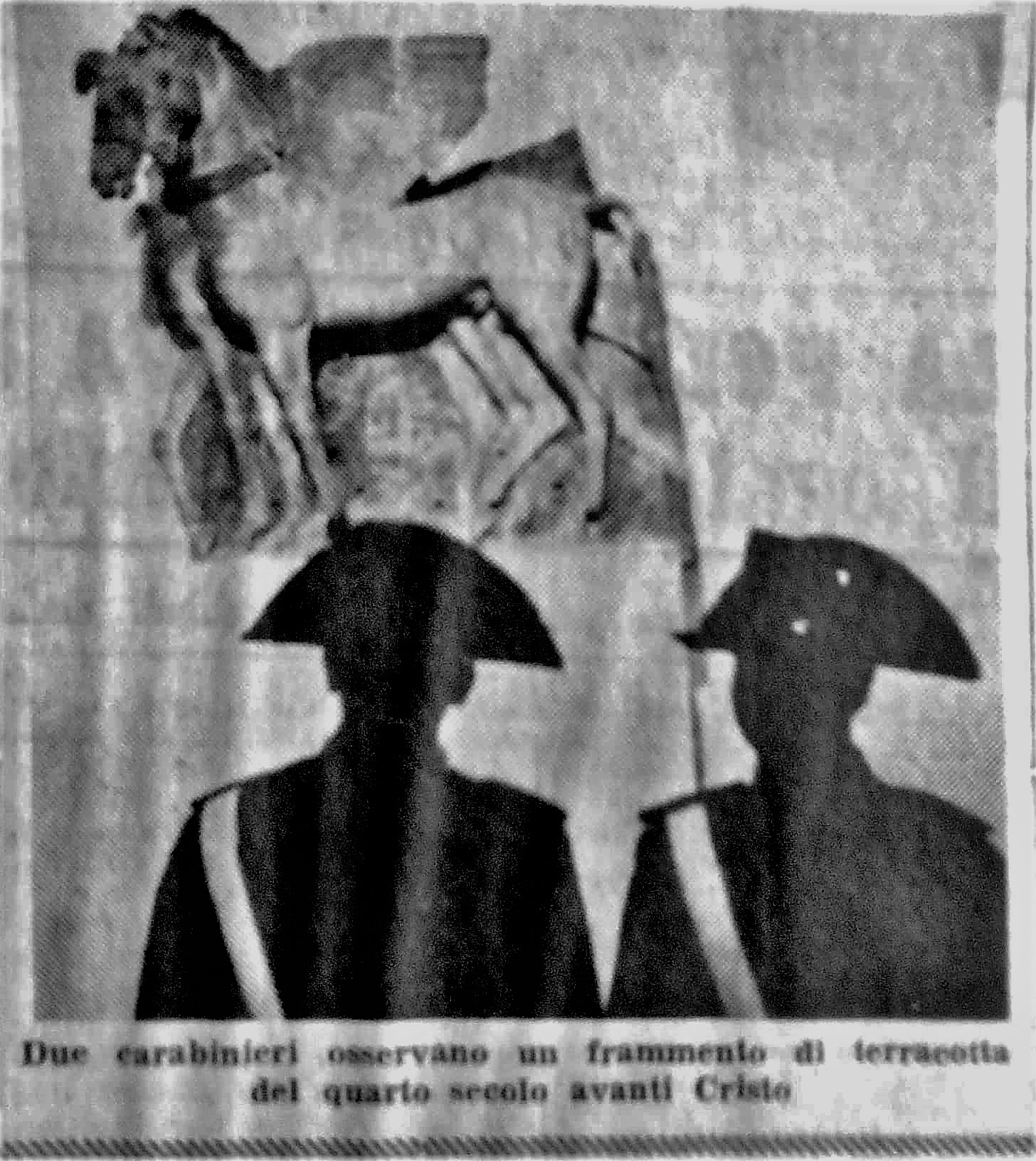

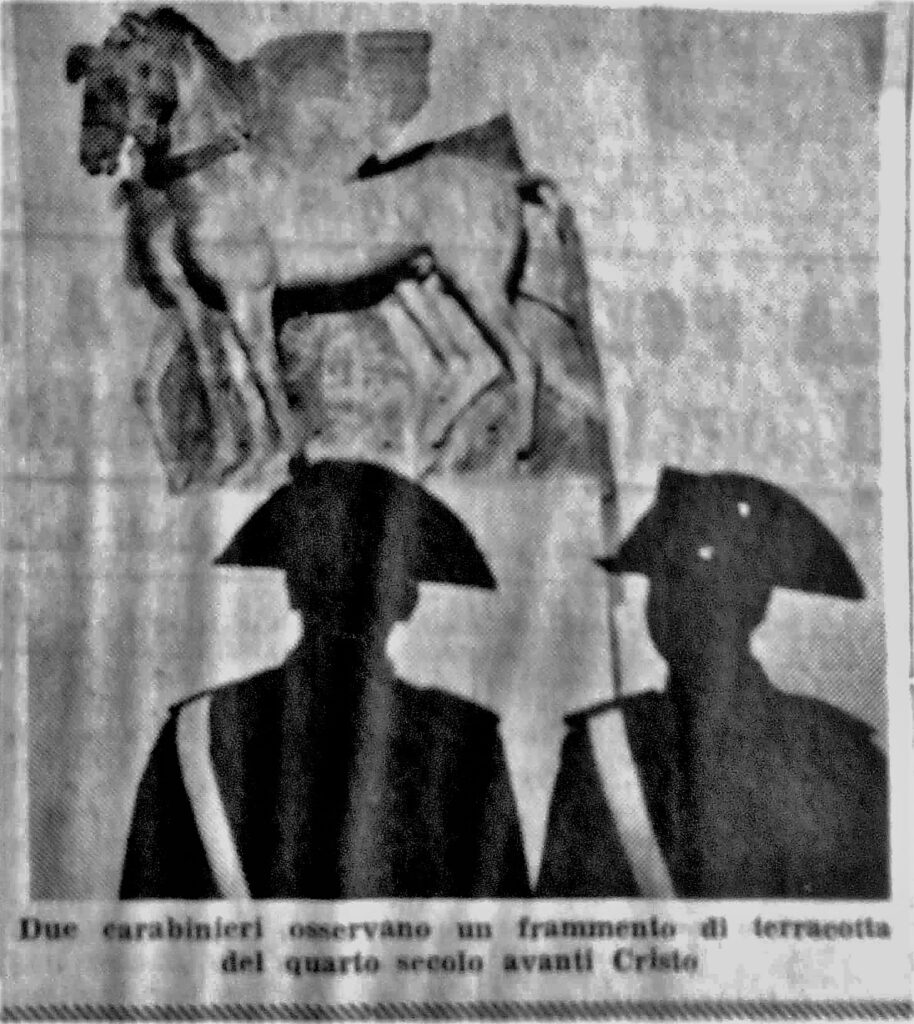

terracotta fragment at the 1955 Exhibition of Etruscan Art and Civilization.

The exhibition was curated by Massimo Pallottino.

In 20th century Italian culture, the Etruscan civilisation has been interpreted as a matter of national and racial identity. We can trace a starting point for this cultural interest: in 1916 the archaeologist Giulio Quirino Giglioli discovered a group of ancient Etruscan statues at the archaeological site of Veii, near Rome. A right-wing nationalist activist and a volunteer soldier in the First World War, Giglioli made his discovery on a temporary military leave from the war front. After the end of the war and his return to private life, from 1919 he engaged himself as a promoter of Etruscan art, as an archaic model for Italian national art. Before and after his adhesion to Fascism, he committed himself to the enhancement of ancient Etruscan art both in his scientific writings and through his new role as director of the national museum of Villa Giulia, in Rome, where the Veii statues had been exhibited. Moreover, Giglioli’s promotion of everything Etruscan proved popular among artists and art critics, directly influencing their turn from avant-garde, modernist formal experimentations to a national way of classicism.

In Italy, this so-called “return to order” was organised by the group of Valori Plastici in Rome and especially by the Milanese group of Novecento Italiano, which was promoted by the art critic Margherita Sarfatti, a close collaborator of Benito Mussolini. Therefore, the Italian “return to order” of modernist art took an openly nationalist and pro-Fascist approach to classicism, as former avant-garde artists were looking to ancient Etruscan, Italic and Roman art as models for a reborn Italian culture and civilisation. Etruscan art came to be used as a nationally and ethnically rooted tradition, against the perception of a cosmopolitan, internationalist and modernist art. In their search for a national classicism, the Italian artists were therefore aligned with the Fascist project of a refoundation of the Italian civilisation against liberalism and socialism, claiming a direct ideological continuity from ancient Italy to the 20th century. Sculptors and painters who associated themselves with the Novecento artistic movement, like Arturo Martini, Marino Marini and Massimo Campigli, were deeply influenced in their works by Etruscan art, which they also studied by visiting the Villa Giulia museum, the archaeological sites and reading scientific works. Even Mario Sironi claimed he was inspired by Etruscan art for his mural paintings, that he presented as an explicitly political, totalitarian art for public buildings.

Certainly, reception of the Etruscan identity had an archaeological, anthropological and linguistic dimension in the history of Italian culture. A new, comprehensive term came to include all the historical, archaeological, anthropological, linguistic and naturalistic research on the Etruscans: “Etruscology”. Modern Etruscology was institutionalised in Italy under Fascism, in the years following the discovery of the Veii statues and the cultural interest for Etruscan art. In 1925 a Comitato Permanente per l’Etruria was founded in Florence, which was later to become the Istituto di Studi Etruschi, and a new chair of Etruscology and Italic Antiquities was established in the university of Rome and entrusted to the archaeologist Alessandro Della Seta. From 1927 a new scientific review, Studi Etruschi, began to be published every year, supplying an authoritative platform for international, scientific studies on the Etruscan civilisation. In 1926 and 1928 two conferences of Etruscology were organised in Florence, where Italian scholars brought together a network of colleagues from different European countries. The main theme of those conferences was the question of Etruscan ethnic origins.

In 19th and early 20th centuries science, the ancient and modern uncertainties about Etruscan origins and the meaning of their language had developed a debate on three main racial theories. Two of them had already been expressed during Antiquity, and were redefined during the 19th century through modern archaeological and anthropological methods. The first, and the most popular among the scholars, was the theory of the oriental origins of the Etruscans, famously theorised by Herodotus. A second interpretation was the autochthonist one, firstly expressed by the ancient Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus, according to which the Etruscans were an Italic, autochthonous people. A third theory, based on a passage of the Latin historian Livy, emerged during the 18th and 19th centuries from scholars like Nicolas Fréret and Barthold Georg Niebuhr, who argued that the Etruscans had come to Italy from the north.

In the late 1920s the different national conditionings in approaching the question of Etruscan ethnic origins became evident. While the majority of non-Italian (especially German and French) scholars believed that the Etruscans had come to Italy from the East, Italian Etruscologists expressed a nationalist perspective on the Etruscan identity along with their adhesion to the Fascist regime. Through their research in art history, anthropology, linguistics, history of religions and folklore studies, Italian scholars shared a representation of the Etruscans as an Italic people, racially and linguistically pre-Indo-European and Mediterranean. In Italy, the international diversity of scientific opinions on the question of the ethnic origins was replaced by a nationalist consensus on the “Italicness” of the Etruscans and their de facto autochthonism as the fathers of the Tuscan and Italian race and civilisation. An isolated, oppositional voice in this cultural context was represented by the imprisoned communist leader Antonio Gramsci. A former student in Humanities, interested in linguistics, Gramsci wrote in his “Prison Notebooks” several critical notes on the nationalist consensus about the Etruscan identity. The Marxist thinker criticised the influence of nationalism in Italian science and expressed interest in the theory of the Nordic origins of the Etruscans, as an alternative to the Fascist, neo-autochthonist consensus.

Another field of Italian culture to be considered, in the analysis of the reception of the Etruscan identity, is literature. Before the First World War and the discovery of the Veii statues we cannot find evidence of a nationalist use of the Etruscans in Italian literature and cinema. In novels and in historical films, they were represented as enemies of the Roman heroes, with orientalist and even macabre attributes. On the other hand, the Etruscans were approached in a regionalist perspective by Tuscan writers and artists. Members of the avant-garde and Futurist groups like Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici claimed in their pre-war writings to be racial heirs of the Etruscans, in order to express a populist, anti-liberal and anti-socialist myth of the Tuscans. This ideology was inherited by Tuscan Fascists, who became interested in the new Etruscology. In particular, several members of the cultural movement of Strapaese, made up by Fascist artists and writers from Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, reclaimed the Etruscan identity. The ideology of Strapaese consisted of a radical opposition to modern and bourgeois society, industry, liberalism, democracy, cosmopolitanism and fashion, and in a fierce, xenophobic and also anti-Semitic defence of an idealised rural, provincial and traditionalist life. In this context, the Etruscans were used as a symbol for a Tuscan, anti-modern identity, and even for radical, provincial Fascism against the perception of a national, Roman and conservative Fascism. Curzio Malaparte and Vincenzo Cardarelli were the main Italian writers to express this Fascist, Etruscan identity in Italian interwar literature.

As had happened before, non-Italian writers also became interested in the Etruscans. The most influential European writer in the literary reception of the Etruscans was David Herbert Lawrence, who lived in Fascist Italy during the 1920s. In his critique of modern, industrial and democratic society, he came to consider the Etruscans as the symbol of an ancient and natural way of life. Lawrence idealised them as a people free in their sexual and artistic instincts, against his perception of a modernity that repressed desire and human nature. He therefore criticised the Romans as the forefathers of this kind of modernity, and the Fascists for claiming to be the heirs of Roman power and violence. Nonetheless, Lawrence idealised the modern Italian people as still Etruscan in their way of life, and thus immune to Fascist ideology and discipline. In the same years, Aldous Huxley also lived in Fascist Italy and was influenced by Lawrence’s theories on history and politics. In Huxley’s short stories and novels as well, we find use of the Etruscans as an anti-modern people, that could be usefully related to his dystopian critique of modernity. In the UK George Orwell openly criticised, from a Marxist perspective, Lawrence’s anti-modern use of the Etruscans as reactionary.

In all of these fields of Italian culture (art, Etruscology and literature) the Etruscan identity was represented in a racial perspective: the ancient Etruscan people were intended as a race, both in a physical and in a cultural sense, and it was put at the very base of the Tuscan and Italian ethnic composition. Even the irrationalist groups in Florence and Rome became interested in the Etruscan civilisation, claiming it to be at the roots of the Italian race and spirituality. In Fascist Italy artists, scholars, writers and irrationalists were therefore generally involved in a regionalist and nationalist use of the Etruscan identity.

The racial dimension of the Italian approach to the Etruscans was therefore well rooted in Italian culture before the ideological influence of German racism in Fascist Italy. Only from 1930 onwards, and especially after the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, did the Italian positive reception of the Etruscan identity have to confront itself with German racial theories. While German nationalist theorists like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Oswald Spengler had expressed positive representations of the Etruscans, among Nazi intellectuals anti-Etruscan theories emerged. Especially Hans Friedrich Karl Günther and Alfred Rosenberg were responsible for spreading the idea that the Etruscans were a Middle-Eastern people, devoted to murders and black magic, responsible for the birth of the Catholic Church. They argued this anti-Etruscan perspective under the influence of anti-Christian and anti-Semitic theories and the theory of the oriental origins of the Etruscans. Nonetheless, these theories were openly criticised within German society. In particular, the Catholic anthropologist and theorist of scientific racism, Eugen Fischer, also argued in 1938 that the Etruscans were an autonomous race of Indo-European descent.

During the 1930s Italian approaches to Etruscan racial identity became deeply differentiated in relation to the different German racial theories. Facing the alliance with Nazi Germany, Italian racists took different positions and can be divided into three competing factions. Scientific racists, pro-German theorists of the Aryan race represented the “biological” faction, who produced the 1938 Manifesto of racist scientists. Irrationalist racists, pro-German theorists of the Aryan race composed the “esoteric-traditionalist” faction. Nationalist and Catholic racists, anti-German theorists of a Roman-Italic or Mediterranean race, formed a “national-racist” faction. Each of these groups had different ideas on the Etruscans as an ethnic component of Italian racial history. Scientific, “biological” racists were influenced by Eugen Fischer’s ideas of a Nordic origin of the Etruscans, and therefore included them within the Italian Aryan race. The pro-Nazi racist philosopher Giulio Cogni, as well as the “esoteric-traditionalist” racist Julius Evola, were both influenced by Rosenberg’s ideas on the Etruscans as an alien body within the Italian race. The main Italian Etruscologists, on the contrary, can be included in the “national-racist” faction. They shared a nationalist, non-Aryan racial identity, tracing back its origins to pre-Roman Italy. In this perspective, and according to the Etruscological “neo-autochthonist” consensus, the Etruscans were considered as an autochthonous people, part of the Roman-Italic race. The main “national-racist” Etruscologist was Massimo Pallottino, a former student of Giulio Quirino Giglioli and his collaborator in Fascist and racist exhibitions such as the Mostra Augustea della Romanità (1937-1938) and the Mostra della Razza project (1939-41). In particular, during the Second World War Massimo Pallottino first expressed his theory on the ethnic “formation” of the Etruscan people, which was later to become, in the post-war years, the most important scientific interpretation of the Etruscan identity in Italy and abroad. By quoting national-racist anthropologists and their political leader, Giacomo Acerbo, Pallottino definitively consolidated the nationalist, “neo-autochthonist” interpretation of the Etruscans as an Italic and Italian civilisation. He criticised other theories on the Etruscan origins, and he argued that Etruscologists should study the process of “formation” of the Etruscan people as a historical process that took place in ancient Italy, from different ethnic backgrounds.

Among Etruscologists, only Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli criticised the nationalist consensus on the Etruscans and the use of racial categories in the interpretation of the ancient past. This scientifically isolated position eventually brought Bianchi Bandinelli to renounce Etruscology as a nationalist science. At the same time, his anti-racist and anti-nationalist critique must be related to his non-linear way to antifascism, which after the fall of the regime led him to adhere to the communist party and eventually to Antonio Gramsci’s Marxism.

After the fall of Fascism in 1943, the German and Allied occupation of Italy and the start of a civil war, a new phase for Etruscology began. Italian scholars themselves were involved in this dramatic war context. In German-occupied Rome, Massimo Pallottino participated in a Catholic and monarchist group of former Fascists that published anti-German propaganda. After the end of the German occupation, he criticised the antifascist democratic parties and openly condemned their attempt to purge the former Fascists like himself from the State. Contrarily to his teacher Giglioli, who was condemned as a Fascist but soon reintegrated in his university chair, Pallottino was never tried for his role in Fascist and racist cultural policy. Instead, he obtained the chair of Etruscology at the University of Rome, maintaining it for the following decades. On the contrary, Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli participated in the antifascist Resistance in German-occupied Florence, adhering to the Italian Communist Party. In the post-war trials, after an initial diffidence, he testified against Fascist colleagues, and called for a renewal of Italian culture, in a communist perspective.

The post-Fascist reception of the Etruscans was soon influenced by the new, Cold War ideological context. During the 1950s Bianchi Bandinelli became one of the leading voices of the communist cultural policy in Italy. His new studies on ancient art were now influenced by Antonio Gramsci’s Marxism. In 1957 he was appointed president of the Istituto Gramsci, a centre for Marxist-Leninist studies supervised by the communist party. In a socialist realist perspective, he criticised Etruscan art as a mere imitation of the classic Greek one, and the interest for the Etruscans as a nationalist, racist and irrationalist myth. On the contrary, Pallottino became the most influential Etruscologist in Italy and abroad, because of his theory of the Etruscan origins, now purged of its Fascist connotation. Moreover, during the 1950s Pallottino engaged himself in constant cultural activism, promoting exhibitions on the Etruscan civilisation across Europe. While imposing his “neo-autochthonist” theory as the main feature of Italian Etruscology, in the years of the Cold War and of Western European economic integration, he ideologically presented the Etruscans as the forefathers of Western Europe.

As regards post-war Italian culture, because of the scientific continuity of Pallottino’s nationalist Etruscology after the war, along with the political and cultural limits of the antifascist “epuration” attempt, the fall of Fascism did not immediately change the reception of the Etruscan civilisation as a matter of national identity. Only after the 1950s can we see a real change in perspective and a new, post-Fascist phase in the history of Italian reception of the Etruscans.

In post-war Italian culture, new approaches to the Etruscan identity were slowly produced, conditioned by the memory of the regime, the war and the Holocaust. In post-war Italian cinema, historical films abandoned the image of a triumphant and imperialist ancient Rome, ideologically represented by the Fascist regime in Scipione l’Africano (1937), and began to depict the Roman rule – in the typical American peplum style – as an arbitrary dictatorship that killed innocent Christians (L’apocalisse 1947, Fabiola 1949, Messalina 1951, Nerone e Messalina 1953). Even if the Etruscans were not represented in those films, we could argue that this new, Catholic and post-Fascist narrative enabled a popular representation of the Etruscans as victims of their violent Roman rulers. Especially in the early 1960s, the emergence of a public memory of the Holocaust stimulated a new kind of private and political reflection on the Etruscan past. In 1962 the Italian Jewish writer Giorgio Bassani interpreted an Etruscan necropolis through the memory of the Holocaust, depicting the Etruscans as an ancient persecuted people, like contemporary Jews. In the 1965 movie Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa…, directed by Luchino Visconti, the Etruscan identity was used as the scenario for the dramatic history of the sons of an Italian Jew killed by the Nazis. Many years later, in 1982, Elie Wiesel also wrote a similar use of the Etruscan identity into his short story L’éternité étrusque, representing an Israeli Jewish survivor and his love for the Etruscans as a persecuted people. Besides, in movies like Il sorpasso, La voglia matta (1962) and later Le vacanze intelligenti (1978) the new, post-war, consumerist Italian people were represented as non-interested in Etruscan identity, and immune to the old, rhetorical and nationalistic education, as well as to the new, intellectual and progressive theories. Such a refusal of Etruscology and the Etruscans is openly theorised, in a clearly antifascist perspective, in 1950s Luciano Bianciardi’s short stories and novels. During the 1960s a new, post-Fascist reception of the Etruscans in popular culture was therefore produced. At the same time, through Pallottino’s relevant and continuous impact on Italian Etruscology, several ideological continuities persisted, especially Italian nationalisation of the Etruscan identity.

The longue durée of interest in the ancient Etruscans as a matter of national and racial identity in 20th century Italy could therefore serve as a case study. It could provide an insight into how modern regional, national and racial identities have been socially constructed through different levels of cultural production, from cinema and literature to archaeology and anthropology. I hope it could therefore stimulate a reflection on cultural and political history, particularly as regards nationalism and racism, through an analysis of our ideological relationship with the historical past.