My current research project Catholicism and the “Negro Question”: Religion, Racism, and Antiracism in a Transnational Perspective (United States and Europe, 1934-1968) — in short US-E AntiRacism — has been funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 794780. This is a project hosted by the DAFIST (Department of Antiquities, Philosophy, History and Geography, UniGe) and supervised by Francesco Cassata since August 2020. Silvana Patriarca (Fordham University, New York) is the co-supervisor on behalf of UniGe’s partner organization.

US-E AntiRacism aims to investigate how the Roman Catholic Church responded to anti-Black racism from the age of ‘overtly racist regimes’, in which White supremacy reached its institutionalized climax, to decolonization, the civil rights era, and 1960s modernization. In particular, my objective is to carry out a first transatlantic analysis on this subject, focusing on Catholic ‘interracialism’ as a peculiar third way between (biologist and Nazi-style) racism and militant antiracism appealing to universal human rights. I will deal with the following key issues: how did interracialism spread and become common sense in Catholicism on both sides of the Atlantic? Did interracialism really challenge traditional race thinking? What were the relationships between US interracial movement and European Catholic colonial and postcolonial culture? I mean to call into question the very notion of ‘Catholic antiracism’ itself, which is often taken for granted in general public opinion and even by significant trends of historiography. My assumption is that both the term and the idea of antiracism struggled to be incorporated within the Catholic mainstream culture. They were not accepted until the Vatican II aggiornamento and the ‘long 1968’ crisis.

My starting point has been the figure of Fr. John LaFarge, the American Jesuit pioneer of the interracial councils’ movement, and his entourage. I would like to make a history of the circulation of these ideals against White supremacy across the European press, the church networks, the intellectual panorama, and mass culture, taking into consideration some specific poles, i.e. Vatican environments and three colonial powers with a Catholic majority (France, Belgium, Italy). Pursuing a cultural and political history of Christian imagery, I will reconstruct the inter-crossing of ideologies, images and practices which shaped a Catholic antiracist network in a broader sense, in order to historicize its emergence, evolution and articulation. I will analyze this interracialist stance by applying a transnational approach, in light of three world-wide known phenomena: Jim Crow segregation in the United States, the apartheid in South Africa, and decolonization. What I would like to do is to show how an increasingly globalized focus on the Black Question gradually framed a new Catholic sensibility, from interracial activism to a real antiracist mobilization.

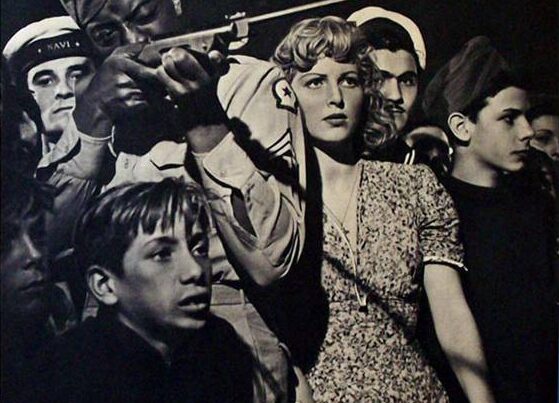

To this end, I believe it is necessary to combine different sources and perspectives: Catholic teaching and theological contributions; newspapers, magazines and journals; missionary press/literature; devotional material; pop culture and visual media.

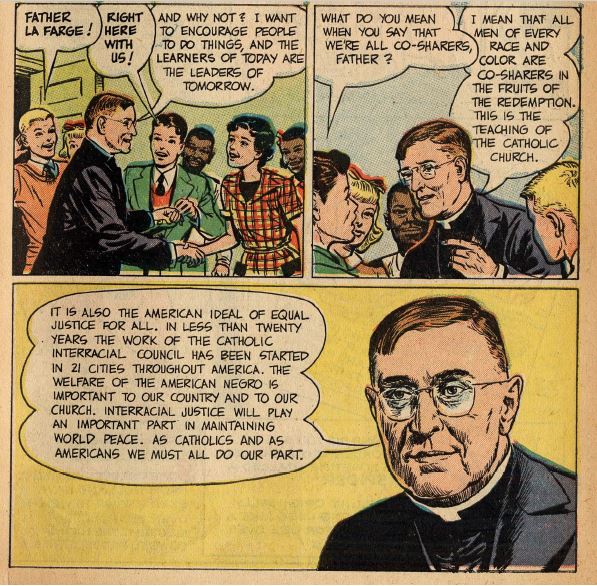

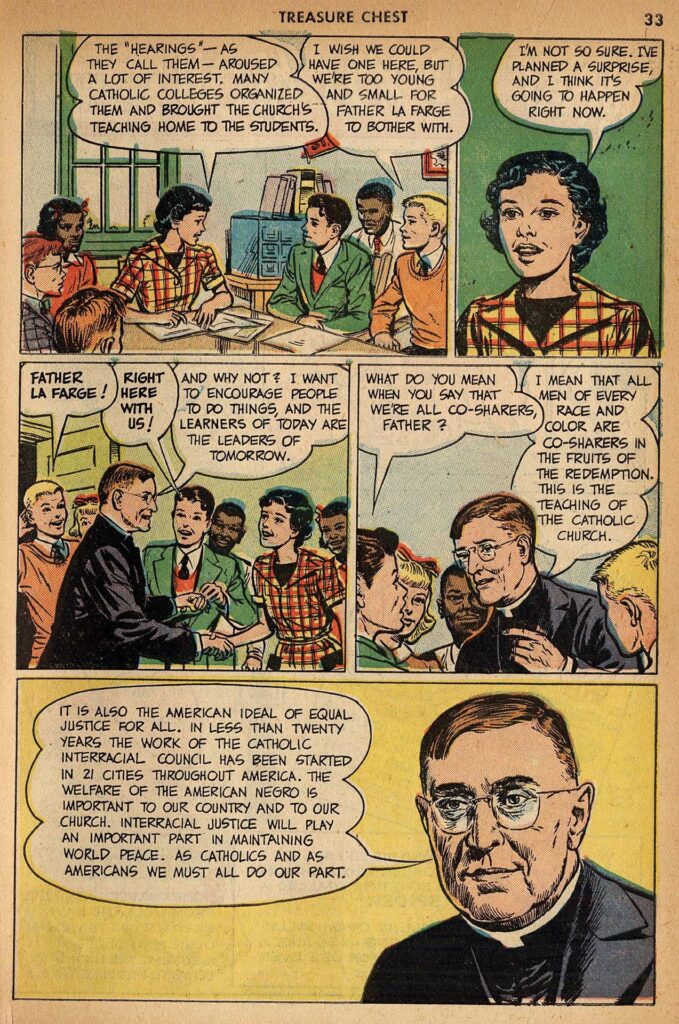

“Catholics in Action”, Treasure Chest vol. 8, no. 15 (March 26, 1953), p. 33. Illustrated by Lloyd Ostendorf.

Courtesy of the American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC (USA). Available at the Catholic University of America Digital Collections http://hdl.handle.net/1961/tc_vol08no15 [Accessed February 19, 2021].

The cartoons are taken from “Catholics in Action”, a serial comic focusing on the leading figures of Catholic social activism, which was prepared under the supervision of the Commission on American Citizenship of the Catholic University of America. This episode was specifically devoted to Father John LaFarge. Even if the main theme is the need for Catholics to demonstrate sincere commitment to finding solutions to the so-called ‘Negro problem’, the story is, no doubt, ambivalent. The comic highlights effectively what David W. Southern called “the limits of Catholic interracialism” (1996). The word ‘racism’ does not appear in these pages, and no reference is made to the burning issue of the US Jim Crow system and desegregation. Furthermore, LaFarge’s struggle against anti-Black prejudice is uncritically portrayed as a harmonious, interracial, non-conflictual program under a White, enlightened, clerical leadership (whereas Black, lay Catholics are thought to be educated and directed to the church’s social teaching). There is no mention of legal equality, or Black protest. By depicting African Americans as the objects of evangelization and not as the protagonists of their own empowerment, the authors deal with “the welfare of the American Negro”, instead of civil rights, saying that this is beneficial for the Catholic Church, US democracy, and world peace. Here is an allusion to interracial mobilization as the best way to prevent Black Americans from falling under Communist fascination and entering violent crime, according to a paternalistic and instrumental attitude. That message avoids to challenge the status quo, and ultimately communicates a racialized image of Black people as culturally inferior and potentially dangerous. In short, interracial justice represents more a means to an end than an end in itself.